This page addresses firstly the topic of Energy Security and secondly explores the value of adopting an integrated energy system design model.

1. ENERGY SECURITY

National security is underpinned by energy security. Energy security, like national security, can only be addressed with consistent bipartisan political support. Unfortunately the topic of energy has become so politicised in Australia, both between the major parties and within the Liberal party. As a result the national interest has been subsumed by both party and personal interests. This is not acceptable.

Whilst Australia is endowed with natural resources, energy security risks across several sectors have increased. Despite this, the current Liberal Coalition Government does not seem to think we have a problem. Unfortunately, energy security is about much more than just a more “reliable” and cheaper electricity supply. It is about our security as a nation, it is about protecting our society and our way of life and, as such, it is a very complex issue.

My latest paper on Fuel Security - This will be published in September 2020 as an Annex in the IIER-A Energy Security Report as a part of the Institutes National Resilience Project.

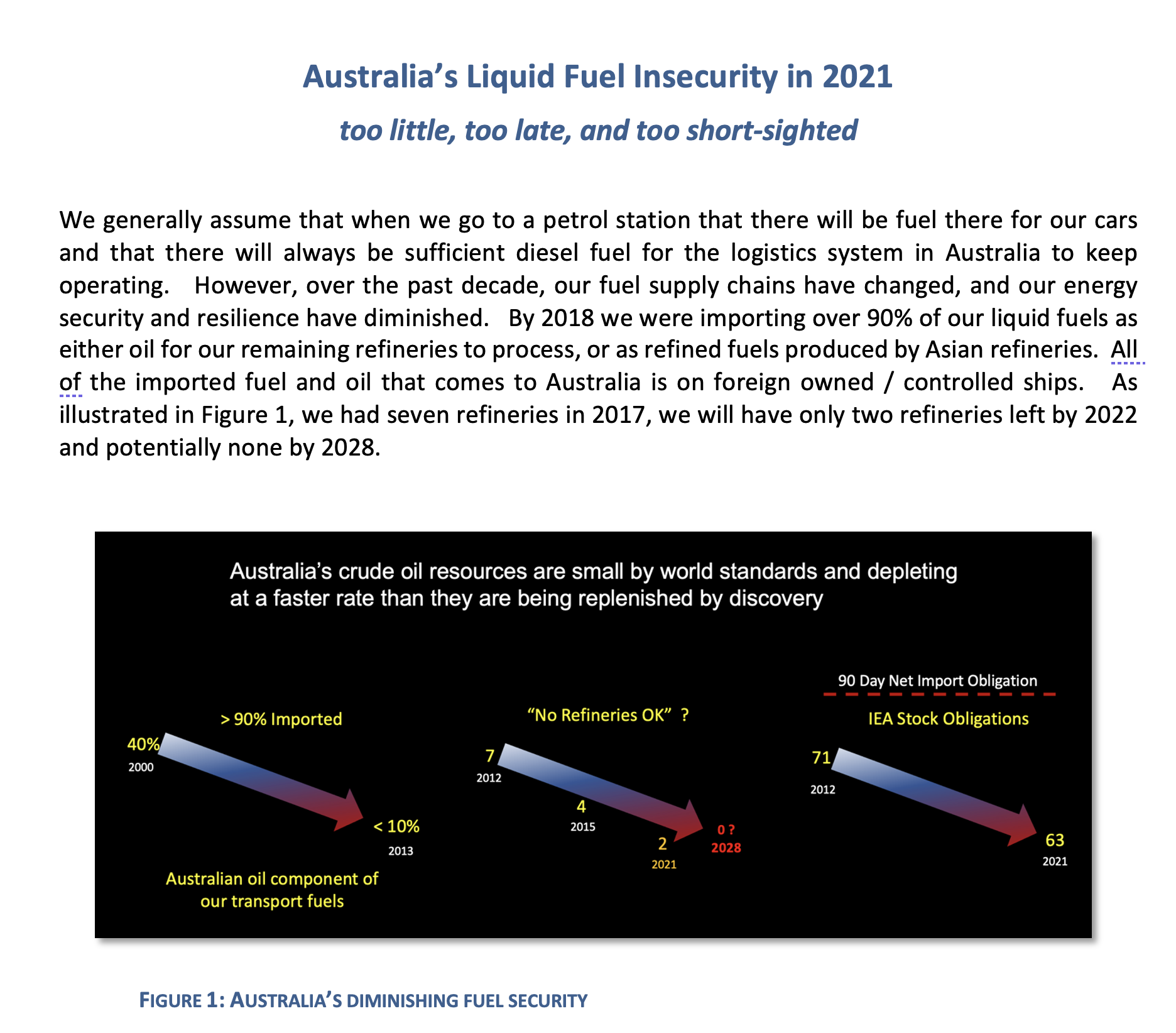

Australia’s Liquid Fuel Insecurity in 2021

too little, too late, and too short-sighted

Australian Governments have largely reacted to crises rather than prepare for foreseeable system failures. Over the past decade, concerns regarding potential energy security risks were often minimised by Government Ministers from both sides of politics, as well as by some Government Departments.

In September 2020, faced with the impending closure of the last four oil refineries in Australia, the Government finally responded to our fuel insecurity. Sadly, the Minister’s announcement was too little, too late, and too short-sighted as only two of the four refineries agreed to accept the Government’s support plan and to be contracted to remain open until 2027.

It may have moved the issue off the agenda for the next Federal election; however, there is no public plan for what will happen with respect to our fuel security after 2027.

MY JOURNEY

I became interested in the topic of energy security when I realised that the assumptions I had made about energy and fuel supplies when I was the Deputy Chief of the RAAF were fundamentally flawed. Accepting that one is flawed is a challenge for any fighter pilot … as I now realise, the problem of flawed assumptions is widespread in our society today. A classic assumption related to fuel security, quoted in the Australian Newspaper in January 2019, is stunning : “The Energy Department said Australia’s low supplies were not a serious concern as there had never been a serious interruption to Australia’s supply.” Using that logic perhaps you should cancel your house insurance if you have never had a fire !

2011

My Own Reality Check …

My own reality check came about when I teamed with Dr Gary Waters in 2011 to research and write this report on Australia’s Cyber Security. In the process of researching that report we found that few organisations, including our own Defence Force, had conducted a cyber resilience analysis of their supply chains, it was merely assumed.

Having by then grasped the scale of our own cyber vulnerabilites, we realised that all essential supply chains were at risk.

2012 / 2013

Having identified concerns in our supply chains, I obtained sponsorship from the NRMA to conduct three studies into fuel security to determine the extent of the problem. My studies confirmed our concerns.

In 2012, the Government issued the National Energy Security Assessment; its’ assessment of fuel security was fundamentally flawed as I discussed in the three reports shown below. The reports are available on the Presentation / Reports page of this website.

2014

Defence Logistics Report

Gary and I then went on to study and write this report on Defence Logistics in 2014. That process did not reassure us either; we concluded that the global nature of supply chains combined with efficiency changes had led to increased systemic risk and reduced resilience in some cases.

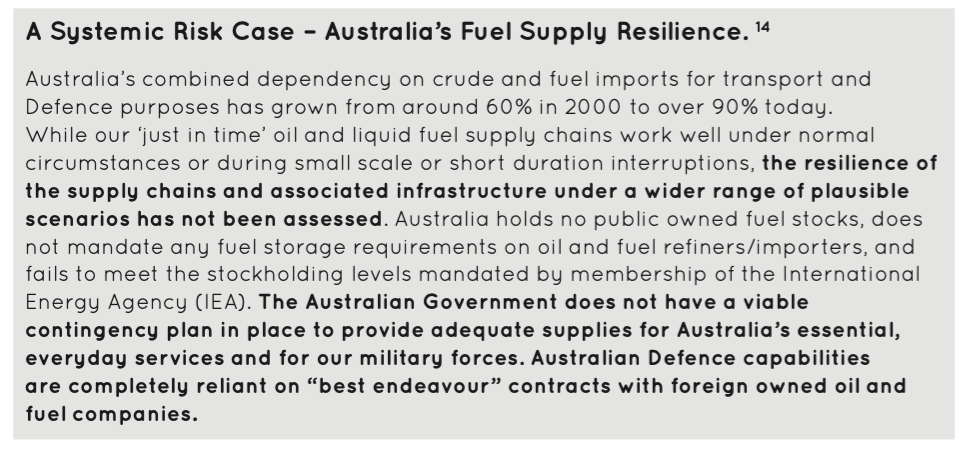

We recommended that Defence needed to take a fresh look at Enterprise risk assessment and the changing nature of logistics support. The systemic risk example we include in our report is shown below.

We still await a response …both from Defence and the Government.

A SYSTEMIC RISK EXAMPLE CONTAINED IN THE DEFENCE LOGISTICS REPORT

2015

The promised 2015 update to the flawed 2012 National Energy Security Assessment was not delivered.

Following the publication of the fuel security reports, a number of concerned Senators initiated the Senate Inquiry below.

The 2015 Senate Inquiry report made the following recommendations:

Recommendation 1 - The committee recommends that the Australian Government undertake a comprehensive whole-of-government risk assessment of Australia's fuel supply, availability and vulnerability. The assessment should consider the vulnerabilities in Australia's fuel supply to possible disruptions resulting from military actions, acts of terrorism, natural disasters, industrial accidents and financial and other structural dislocation. Any other external or domestic circumstance that could interfere with Australia's fuel supply should also be considered. This recommendation has still not been implemented, despite a further Parliamentary Joint Committee March 2018 recommendation to do so.

Recommendation 2 - The committee recommends that the Australian Government require all fuel supply companies to report their fuel stocks to the Department of Industry and Science on a monthly basis. This recommendation was eventually implemented in 2018.

Recommendation 3 - The committee recommends that the Australian Government develop and publish a comprehensive Transport Energy Plan directed to achieving a secure, affordable and sustainable transport energy supply. The plan should be developed following a public consultation process. Where appropriate, the plan should set targets for the secure supply of Australia's transport energy. This recommendation has been ignored by the Government.

2016 / 2017

The promised 2015 National Energy Security Assessment

… was still not delivered.

2018

The promised 2015 National Energy Security Assessment was still not delivered.

In March 2018, the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security published an Advisory report on the Security of Critical Infrastructure Bill 2017.

The first recommendation of that report was : “The Committee recommends that the Department of Home Affairs, in consultation with the Department of Defence and the Department of the Environment and Energy, review and develop measures to ensure that Australia has a continuous supply of fuel to meet its national security priorities. As part of developed measures, the Department should consider whether critical fuel assets should be subject to the Security of Critical Infrastructure Bill 2017. The Committee considers that the Department should conclude this review within 6 months. The Department should brief the Committee on the outcomes of the review following its conclusion.” The response to that recommendation was due in December 2018. The Department of Energy failed to deliver the report to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security in December 2018.

2019

ABC News Article Jan 19

Sometimes you just have to say what you really think !

On 4 April, 12 months after the Joint Committee recommendation, the Department of Energy published their interim Liquid Fuel Security Review report. It failed to achieve the task. The interim report was a positive step in the right direction; however, it revealed how little analysis had been conducted by successive Governments to date with respect to how our supply chains work and the risks we face in a rapidly changing global environment. The authors deduce the following “findings”:

• Fuel shortages are not something that most Australians have experienced.

• Australia manages fuel differently from other countries.

• Australia is heavily reliant on imports of liquid fuels, and this is unlikely to change.

• Australia is an energy superpower, but not when it comes to oil.

• Australia needs to keep pace with global trends, otherwise we risk being left behind with ageing infrastructure and potentially more limited supply of oil.

• Burdensome administrative requirements of the Liquid Fuels Emergency Act are likely to delay an effective Government response in an emergency. (This is a serious issue - in other words we do not have an effective framework through which Government can respond rapidly to a fuel supply emergency.)

• There is no overarching understanding of the whole liquid fuel market in Australia and how different parts interact with each other. The Department is now developing a model of the fuel market and its supply chains.

• “Australia is potentially exposed to potential fuel supply disruption in Asia and the Middle East. While it is extremely unlikely, ongoing tensions in the Middle East may affect oil production” (recent developments in the Middle East would suggest that this assessment was somewhat optimistic … albeit full of “potentials” ! )

The report discussed further work that needs to be done and “guesstimates” that the final report will be delivered to Government in the second half of 2019 (some 12 months late.) By that time, the 2015 National Energy Security Assessment will be 4 years overdue.

In August 2019 Energy Minister Angus Taylor announced that the government was negotiating to buy millions of barrels of oil from America's fuel reserve under an emergency strategy to lower the risk of Australia plunging into an economic and national security crisis. What he was trying to do is to meet our obligations as a member country of the International Energy Agency (IEA), which requires us to hold 90 days of net import of fuel and oil. We are the only member country that does not meet our obligation. However, this obligation does not mean we would actually hold 90 days of diesel and 90 days of unleaded and 90 days of jet fuel. The 90-day figure is just an accounting measure. For example, we had about 21 days of diesel stocks as of April 2019 (but it has been as low as 12 days in the past three years.)

Will this "deal" make any real difference to our own energy security, given that we import more than 90 per cent of all our transport fuels as either oil or refined product? Will it mean there is significantly less risk for Australians running out of fuel in days, or weeks, in the event of a supply disruption? Unfortunately, it will not. What we are seeing here is marketing instead of real action and a clever accounting move to avoid having to address our real fuel security problem.

Paying for US oil stocks, which will stay in the US, is a move to try to meet the IEA measure set in the 1970s. A lot has changed since then. The security of our fuel supplies has become much more complex – a simple move to count oil in a foreign country as our own will do very little for our domestic energy security. Don't forget that we would have to ship it to Australia (a 20-day process, according to the minister) then refine it and then get it to the bowsers. This is a long process given the reality of very low stock levels in our country. Who would ship it and who would refine it in Australia?

We only have four oil refineries and, as at August 2019, one of those was operating at a reduced production rate whilst maintenance was carried out. We used to have 100 Australian-flagged ships ... we now have 13 flagged ships, and that number is diminishing. We now depend on foreign-owned ships to bring oil and fuel to Australia.

Our government seems to think the foreign-owned "market" can be left to manage our energy security for us, shipping foreign-sourced oil and fuels in foreign-owned ships. This is a significant risk in this day and age. The oil "deal" announced by the Energy Minister will not change these facts.

Most other developed countries take a far more rigorous view of their energy security. Our government does not mandate minimum stock levels for our fuel companies to hold; it is left to the "market". The government's own interim fuel security report published in April this year admitted that we do not have an adequate model of how our energy supply chain works. The report also stated that Australia may be left behind as the world moves away from oil-based fuel to other forms of transport energy. How does buying oil stocks that are stored in the US address these issues?

The bottom line is this: We do not have a coherent energy policy, we have not done a comprehensive risk analysis of our fuel supply chain, we have not updated our national energy security assessment since 2012, and Minister Taylor seems to think buying some oil stocks in the US will fix our fuel security.

My advice to Australians is that it will be too late to think about this when you are queuing at a petrol station for rationed supplies of fuel, or when the local supermarket or chemist hasn't received any food stocks or pharmaceuticals. Fuel security is a key component of our energy security. Energy security is the foundation of our national security.

We do not have a national security strategy for Australia and we do not have an adequate level of energy security.

Future generations will look back at this period in our history and see a lot of marketing and spin, but a complete absence of political leadership and coherent policy. What kind of a legacy is this to leave to our grandchildren?

This section is an edited version of my article in the Sydney Morning Herald of 6 August 2019.

So, just to recap the situation we are in as of 2019 … does this look like a resilient state of affairs given the recent drone strikes on the Saudi oil refineries ?

The story continues … very slowly

Australia’s Liquid Fuel Security

Presentation to the Liquid Fuel Security Conference - 27 October 2020

2. THE NEED FOR INTEGRATED ENERGY SYSTEM DESIGN

In 2018 I began exploring the broader issue of energy security, beyond my initial fuel security focus. I subsequently made a presentation on the topic to the RAAF Airpower conference in early 2018 and published a related article in the Australian Defence Magazine in September 2018. I also had the opportunity to meet twice with Professor Alan Finkel, the Chief Scientist of Australia, to discuss the model of “5th Gen Integrated Energy Design” I had proposed, based on the design approach taken by the RAAF under Plan Jericho.

THE LACK OF A SYSTEMS DESIGN

Energy issues are so intertwined with other security developments that we cannot afford to ignore them. Solving the energy security issues of today will not be sufficient; we need to anticipate the energy systems of the future. As we try to address the energy transition challenge, there is an opportunity to learn from others who are making some progress in systems integration. I suggest that there may be some design thinking that we could adapt from some Defence Forces, that are in the process of transforming to an integrated design force model, and apply it to the challenge of integrated energy system design in Australia. The following is a summary of the Energy Presentation and report posted on the Reports section of this website.

There has been much publicity in recent years about the transformation of our Defence Force into a “5th Generation” Force. The initial discussion centered around the RAAF’s Plan Jericho, with subsequent discussion of a 5th Generation Defence Force. The concept of a 5th Generation force was not just about acquiring 5th Generation platforms. It was about using the opportunity of 5th Generation technologies to integrate the existing 4th Generation platforms, to improve their capability and then, in turn, to amplify the capability of the new 5th Generation platforms. It was a change in the way of thinking about integrated design, it was about a cultural shift away from the platform towards thinking at the program or systems level.

If we apply the construct of “Generations” of capability to the energy sector we could perhaps describe biomass as 1st Generation, Coal as 2nd Generation, Oil and Gas 3rd Generation and Nuclear and Renewables as 4th Generation. I have referred to the latest energy technologies as 4th Generation because they are being developed and fielded the same as we fielded 4th Generation platforms, such as the F/A-18.

Similar to what was done in Defence, 4th Generation energy systems are being acquired in component pieces, not as a part of an integrated system. This has led, as in the case of the South Australian Electricity blackouts, to systems failures. The question is, can we think about a model for a 5th Generation integrated energy system?

The technologies necessary to implement a 5th Generation energy system exist today. We just lack the integrated design approach.

An example of such an approach can be shown in combination with solar and wind systems. Despite having the highest deployment of solar on domestic houses in the world, solar and wind systems provide only about 1% each of our energy supply. The problem is that together they can at times provide more energy than is required; in some cases, it is the local electricity infrastructure that cannot handle the amount of energy that can be produced. At other times, solar and wind systems cannot meet the energy demand and thus they are blamed for supply failures.

Is there a possibility of utilising the energy produced by solar and wind systems differently? There are a range of excellent academic studies that have highlighted the value of pumped hydro systems to store renewable energy. At scale, pumped hydro seems to be the only viable solution, but at considerable cost and time for implementation. There are also examples of small scale, regionally-based renewable energy storage systems such utilising Hydrogen, which can also be used to produce a range of energy products. Hydrogen, in this case, is the medium to produce both a time and mode shift of renewable energy. Hydrogen could be used for power generation, for fuel cells in vehicles and trains, to produce ammonia, to supplement gas supplies and to produce gas. It could also provide a significant export resource to countries such as Japan, where Hydrogen imports have been identified as a Government energy policy priority.

Whilst not the panacea for Australia’s energy needs, Hydrogen, as but one example, could be an important component of an integrated energy system, particularly as it could employ excess renewable energy capacity. The production and transformation of energy in regional or sub-regional networks using such “energy integrators” could exploit an energy resource that is not utilised to maximum effect today. It is about integration, resilience, economics, energy security and scalability. It is about integrated design. A more comprehensive discussion of this topic can be viewed in my presentation to the 2018 RAAF Air Power Conference.

Story to be continued …